One Nation, Many Feeds

How GenAI takes the algorithmic echo chamber to the next level and why it matters for how we understand each other

Have you ever had this happen? You meet someone new, a friend of a friend, a neighbor, the family of your new partner. You talk, maybe hang out a few times. You notice the little things: they take good care of their pets, they are patient with kids, they help carry groceries for the older guy down the street. You walk away thinking, these are good people.

Then you connect online, a Facebook friend request, an Instagram follow, or whatever the young people are doing these days. And there it is: a post, a reshare, the thing that stops you cold.

It is clear they voted for so-and-so when you voted for such-and-such, and the gap between you feels suddenly enormous. They feel differently about [insert hot-button issue here], and you are rethinking everything. Were they actually being kind, or just playing nice? If they support such-and-such, you know what those people value, and it is not okay.

Part of what is happening is baked into the system.

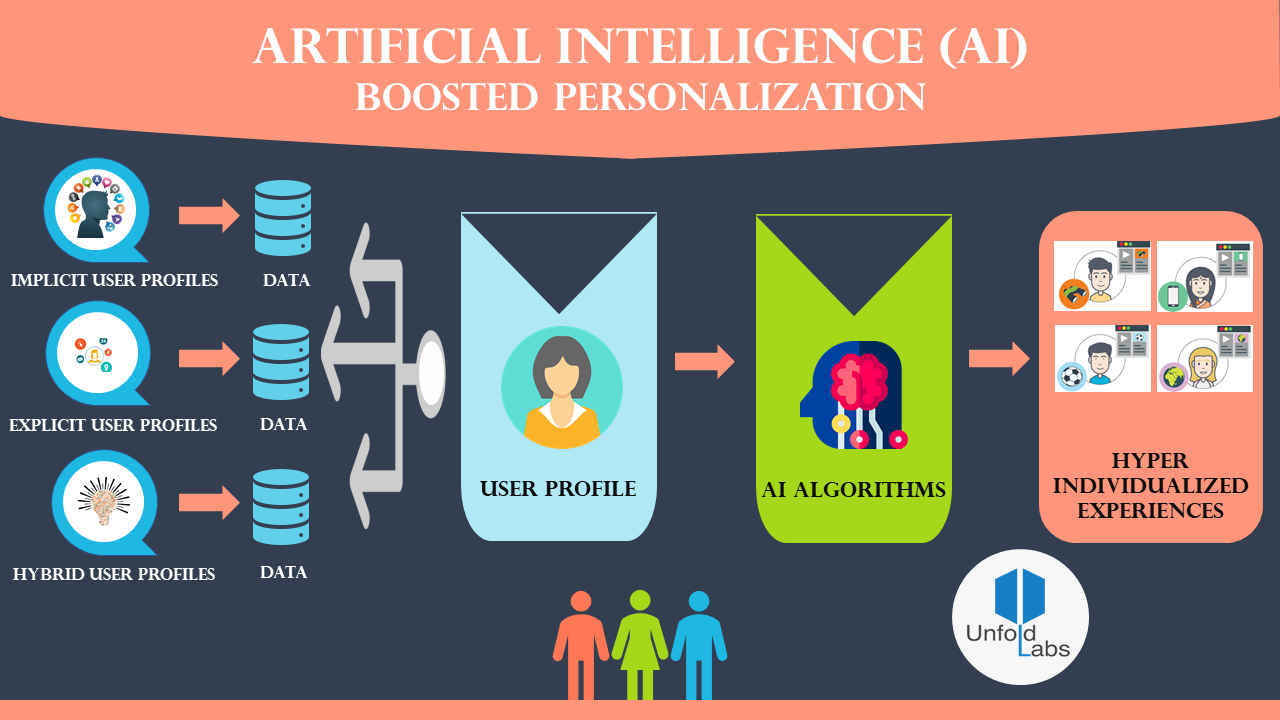

The internet no longer shows us the same world. Personalization means my feed and your feed can be entirely different realities, fine-tuned by AI-driven ranking systems that learn what makes us stop scrolling.

Over time, that creates a feedback loop, a softer version of an echo chamber, where we keep seeing more of what reinforces what we already think and less of the context that might complicate it. And when we are behind a screen, sometimes anonymous, sometimes just far away, the guardrails of empathy come off more easily. And now a new layer is arriving: generative AI. The feed no longer just chooses what to show us; it can make new posts, images, even voices that match our tone and tastes. Personalization is moving from curation to creation.

There was a time when this was not the case. We saw roughly the same stories, heard the same headlines, and argued from the same set of facts, even if we disagreed on what those facts meant. That shared foundation has been splintering for decades, first with cable news, then with the internet, and now with AI-powered feeds that make every version of reality bespoke.

The question is: how did we get here, and what does it mean for how we see each other now?

From Common Ground to Fractured Feeds

In the 1970s, nearly every household tuned into one of three major broadcast networks — the American Broadcasting Company (ABC), the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), or the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) — each evening, read the local newspaper, and maybe listened to a handful of radio stations. Biases existed, but most people were watching the same story unfold.

Part of what kept that coverage relatively balanced was the Fairness Doctrine, a 1949 FCC policy that treated over-the-air radio and TV stations as public trustees. Because they used the publicly owned broadcast spectrum and held government licenses, they were expected to serve the whole nation and, locally, the communities where they were licensed. The doctrine required them to air coverage of important public issues and to give competing viewpoints a fair share of airtime. It applied only to broadcasters using public airwaves, not to cable channels, which didn’t face the same licensing rules.

That landscape began to shift in the 1980s. CNN launched 24-hour news in 1980, creating a constant stream of coverage that could fill the gaps between major events. Fox News and MSNBC followed in 1996, building loyal audiences with distinct ideological leanings. In 1987, the Fairness Doctrine was repealed, removing the obligation to present opposing views and clearing the way for the rise of opinion-driven talk radio. Rush Limbaugh’s nationally syndicated show, starting in 1988, became the template for personality-driven political commentary.

The internet didn’t just open the door to more voices, it splintered the conversation into countless separate rooms. In the early 2000s, blogs, forums, and online communities let people bypass traditional outlets entirely. You could find your people anywhere in the world, and tune out everyone else. This was still largely self-directed, you had to seek out your corner.

Social media flipped that dynamic. Your corner came to you. Ranking algorithms determined what you saw first, starting with small tweaks like showing posts from friends you interacted with most. Over time, these systems learned from every click, pause, and reaction. They began predicting which posts would keep you engaged and quietly filtering out the rest.

What rises in such feeds tends to be what keeps us engaged, and research helps explain why certain content wins that competition. Using language that mixes moral values with strong emotions makes posts spread more widely on social media, false news travels farther and faster than true news in part due to novelty and emotional punch, and online social learning reinforces outrage by rewarding it with likes and shares — teaching users to post more of it.

Design choices can amplify this. Internal Facebook documents revealed that, starting in 2017, emoji reactions were weighted more heavily than likes, with the “angry” reaction counted five times as much (though this was later rolled back), boosting provocative material that elicited strong responses. Emotion doesn’t just spread content; it spreads through people. In a massive research study with nearly 700,000 Facebook users, reducing positive or negative posts in feeds led users to post in the same emotional direction, clear evidence of large-scale emotional contagion.

Politics makes the pattern sharper. Researchers found that Twitter’s algorithmic Home timeline consistently boosted political posts compared to a simple chronological feed. The algorithm amplified content from the mainstream political right more than from the left, but the bigger takeaway is that an engagement-driven, AI-ranked feed gives you a different version of politics than you’d see if posts were shown strictly in time order. And a 2018 study from Data & Society found that recommendation algorithms on YouTube can lead users toward more radical political videos over time, not because of an explicit political agenda, but because those videos kept people watching longer.

None of these systems have a rule that says “show extreme views,” but engagement-optimized AI can still elevate them indirectly. Content that provokes outrage or delivers the sharpest possible take is more likely to make you click, comment, or share, and therefore more likely to rise in the rankings. Over time, a feedback loop forms: you see more of what you engage with, your behavior further trains the model, and your feed narrows to a subset of voices.

Put together, you mostly encounter your people and their most charged takes, while the other side appears in its most extreme form. The AI hasn’t chosen a side, it has learned to prioritize whatever keeps you looking, reacting, and returning. And that is how the neighbor you once knew offline can appear in your feed as a caricature, distilled to the single post most likely to provoke you.

The Distance Between Us

When every feed is personalized to me, it quietly rewires how I see you.

All of this might sound like a technical shift, an algorithm here, a tweak there, but the effect shows up in daily life. When my version of the world and yours no longer overlap much, it’s not just that we disagree on solutions, we often can’t agree on what the problem is.

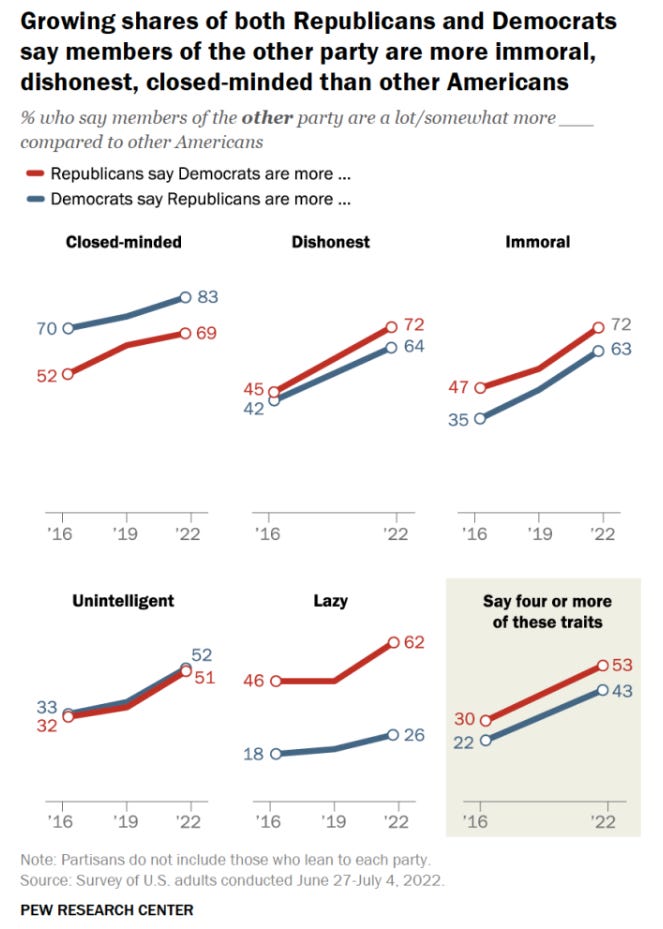

That gap plays out in subtle and not-so-subtle ways. Maybe it’s a tense family holiday where politics feels like a live wire. Maybe it’s noticing a neighbor’s yard sign and suddenly feeling less comfortable making small talk. Research from the Pew Research Center shows that partisanship in the U.S. has deepened dramatically over the past two decades, with fewer people holding mixed political views and more expressing highly negative opinions of the other side.

It’s not just politics. Social psychologists have long documented the online disinhibition effect — the way people behave more freely, for better or worse, when shielded by a screen. Some of that disinhibition can be benign, like greater openness or self-disclosure, but it can also turn toxic, fueling rudeness, hostility, and cruelty. John Suler identifies factors that drive this shift, including anonymity, invisibility, delayed responses, and a sense that the online world is separate from real life. These conditions strip away cues that normally trigger empathy or restraint, making it easier to fire off an emotional hit and run.

When platforms layer engagement-optimized feeds on top of those dynamics, the effects can grow exponentially. Anger spreads faster than joy online, especially through weak ties, which makes distant or disliked voices more combustible.

What is more, the same algorithms that make your feed feel relevant also remove the friction of encountering people unlike you. In offline life, you can’t walk down the street without brushing past different perspectives, life experiences, and values. Online, it’s entirely possible to go weeks or months without seeing a meaningful challenge to your worldview.

That narrowing of exposure doesn’t just polarize, it erodes trust. And when trust goes, connection follows.

How Generative AI Builds Bespoke Realities

Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg now frames this next phase as personal superintelligence, assistants that learn your goals and style and act on your behalf:

“Meta's vision is to bring personal superintelligence to everyone. We believe in putting this power in people's hands to direct it towards what they value in their own lives.

This is distinct from others in the industry who believe superintelligence should be directed centrally towards automating all valuable work, and then humanity will live on a dole of its output. At Meta, we believe that people pursuing their individual aspirations is how we have always made progress expanding prosperity, science, health, and culture. This will be increasingly important in the future as well.

The intersection of technology and how people live is Meta's focus, and this will only become more important in the future.

If trends continue, then you'd expect people to spend less time in productivity software, and more time creating and connecting. Personal superintelligence that knows us deeply, understands our goals, and can help us achieve them will be by far the most useful. Personal devices like glasses that understand our context because they can see what we see, hear what we hear, and interact with us throughout the day will become our primary computing devices.”

For most of the last two decades, personalization meant choosing from the existing pool of human-made content. An algorithm decided which article, video, or post landed at the top of your feed, but what you were shown had been created for a broader audience.

Generative AI changes that. Instead of selecting from what’s already out there, platforms can now produce entirely new text, images, audio, or video in response to your interests, history, and behavior. The same systems that once learned which stories kept you engaged can now invent the next story just for you.

This personalization is not just about topic; it is about tone, style, and emotional triggers. Studies show that AI can craft more persuasive, personalized messages than generic ones, and that LLM-generated arguments can influence attitudes in political contexts. Because the marginal cost of generating content is near zero compared with traditional production, there is no reason to stop at one version; many variants can be tailored to different users.

This is where the risk shifts from echo chambers to bespoke realities. Instead of only reinforcing what is already in our feeds, AI can fabricate narratives calibrated for each of us individually, which makes it harder to know whether we are living in the same world at all.

This is not theoretical. AI-generated news articles have already appeared in mainstream outlets and required corrections (CNET’s AI-written finance pieces), celebrity deepfakes have been used in deceptive ads (Tom Hanks dental ad deepfake), political voice-clones have targeted voters (Biden robocall in New Hampshire), and AI-generated “breaking news” images have briefly moved markets (fake Pentagon explosion image). AI-powered news apps now also personalize and summarize coverage, blending editorial choices with generative summaries. Once this synthetic material enters the same feeds that already filter reality, the effect compounds: you are not just seeing a narrow slice of the world, you may be seeing a fabricated one designed to fit neatly within that slice.

Personalization makes this especially potent. Research on cognitive confirmation bias shows that people are more likely to accept false information when it aligns with their preexisting beliefs. Generative AI can now produce tailored misinformation at scale, shaped to match the tone, style, and talking points most persuasive to a specific audience, and do it instantly, without the distribution bottlenecks of the past.

The danger isn’t only that people will believe fake things. It’s also that people will stop believing real things. Scholars call this the liar’s dividend: as deepfakes and other AI-generated forgeries become common enough, they give cover to dismiss inconvenient truths as “probably fake”. This undermines trust in legitimate journalism, public institutions, and even personal relationships.

If the first wave of the internet fractured the public square, and social media built bespoke realities, generative AI is on track to build entire bespoke worlds, each one optimized for engagement, shaped by your history, and increasingly difficult to fact-check in real time.

That said, generative AI doesn’t only pose risks. When thoughtfully designed and purposefully aligned with fact-based learning, it can also correct misunderstandings. A 2024 randomized controlled trial found that AI-mediated dialogue reduced belief in conspiracy theories by nearly 20 percent, with sustained effects over two months. Another study using an AI “street-epistemologist” chatbot saw similar reductions.

The catch is intention: when a product is built to reward engagement rather than accuracy or perspective-taking, those corrective potentials may be sidelined.

Back to the Sidewalk

You see your neighbor again, the one who helped carry groceries for the older guy down the street. You know now that your feed is a fun-house mirror, not a window. You could let that one post define them, or you could start with a question and a walk around the block. Small, human choices still matter.

A few to try this week, simple and concrete:

Choose one daily news touchpoint that isn’t algorithmic by default (e.g., a trusted newsletter or a direct visit to a site’s Latest page) and use it for seven days. Notice how your mood and assumptions shift.

Add five thoughtful voices you usually disagree with, not trolls, and actually read them. (Aim for people who argue in good faith; mute the rage-bait.)

Before you reshare anything, open it, sit with it for ten seconds, ask what it is trying to make you feel. If it’s outrage, add context or skip the share.

When a post makes you angry, write a reply and save it to drafts, then ask one person offline what they think before you post.

When you know something is AI-generated, say so. If you’re not sure, ask where it came from and how it was made. And if you still can’t tell, take a minute to check the source (who published it, when, and in what context) before deciding whether to pass it along.

Platforms and policies matter, and you have a vote there too. But the bridge back to each other starts close to home, with how we scroll, how we speak, and how we show up. When every feed is me, the work is to make room for you.

(I'm writing from Brazil)

Yesterday I finished Jill Lepore's long book - These Truths - and this publication here on Substack helps to round out the panorama beyond that book (since it covers the year 2017).

Indeed, the intertwining of communication techniques and politics produces sweeping transformations. And when political leaders organize their policies based on this context, we all suffer in some way.

Thank you for providing such excellent writing.

Thanks. That was a lot of work writing. Will share and think about it more.